THE CONSTITUTION OF JAPAN

Promulgated on November 3, 1946

Came into effect on May 3, 1947

Article

96. Amendments to this Constitution shall be initiated by the Diet, through a

concurring vote of two-thirds or more of all the members of each House and

shall thereupon be submitted to the people for ratification, which shall

require the affirmative vote of a majority of all votes cast thereon, at a

special referendum or at such election as the Diet shall specify.

Amendments

when so ratified shall immediately be promulgated by the Emperor in the name of

the people, as an integral part of this Constitution.

Essay Written by OKANO Yayo

On June 14, 2013, I participated in a panel

discussion held in Sophia University as part of a symposium to oppose amendment

of the Constitution without thorough discussion. The symposium also marked the

start-up of the Association of Article 96.

HIGUCHI Yoichi, representative of the

Association, gave the keynote speech of the symposium, titled “What does it

mean to ‘amend’ Article 96 in terms of constitutionalism?” “We cannot change Article 96 by using Article

96,” said Higuchi in his speech, introducing the philosophical argument

concerning the right to establish the Constitution. He also said “It’s just like a back-door

admission, or like a baseball player in a slump asking for a change of the

rules so he can have one more chance after a strikeout.” Through these humorous analogies, he made it

clear how Prime Minister ABE Shintaro’s draft for amendment violates the idea of constitutionalism

itself.

I still remember very well that Abe stated

in Kyoto in March, 2012, when his party

was in the opposition, “It would be absurd if the Constitution could not

be amended just because of one third of the Diet members. I’d order such arrogant politicians out of

the Diet.”

According to Higuchi, it is quite arrogant of Abe himself to treat one

third of the legitimately elected representatives like that. “Abe doesn’t even know how to use the word

“arrogant,” Higuchi added in his comment.

Abe certainly didn’t even understand the significance of the provision

of Article 96 which requires much deliberation so that two thirds of the Diet

members can be convinced to agree.

It is Article 13 that Higuchi, an active

leader of constitutional studies for many years, singles out as the most

important article of the Constitution.

The article requires the state to “respect individuals.” The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan

(hereinafter, LDP) intends to change “individuals” to “mankind” as a whole

without appreciating the significant historical value of the individual at all

in attempting to change the Constitution for the worse.

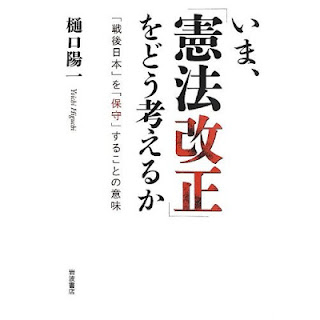

(How We Should Consider Amendment of the

Constitution: The Significance of Conserving “Postwar Japan”—a book authored by

Higuchi, published in May, 2013.)

After his keynote speech, I joined a panel

chaired by SUGITA Atsushi, a scholar of politics, together with YAMAGUCHI

Jiro, another scholar of politics, KOMORI Yoichi, a scholar of literature, and

HASEBE Yasuo, an expert of constitutional studies.

The following is what I said as one of the

panelists, with major focus on “we” in relation to the Constitution. My speech was based on three perspectives;

(1) the relationship between the people (“we”) and democracy, (2) issues of us women, and (3) our own being as secured

by the current Constitution.

(1) As those who insist on having our own

constitution made by ourselves have been arguing, it might be the prerequisite

of democracy and people’s sovereignty that “we” determine the Constitution

under a democratic system and live in conformity with a Constitution we have

enacted by ourselves. But the principle

of this “democracy” has its own paradox. Based on the universal truth that

people are born and destined to die, we can assume the “we” of today are not

the same as the “we” of tomorrow.

If so,

fundamental difficulties are inevitable as to whether we should hold a

referendum every day so that it properly reflects the ever-changing views of

the people. And of course, “we,” having

various views and opinions, will be divided on a critical issue like the basic

principles of the state as is obviously shown in the current

controversies. So long as the

Constitution is the paramount legislation, it is by no means acceptable to

change an article and amend it through simplistic democratic procedures, namely

a rule of majority.

To put this into somewhat more concrete

terms, I would like to refer to the function of a Constitution serving as a

fortress to shelter social minorities.

The Constitution is not something to be altered by majority opinion of

anytime, but it has rather been a last resort for the people who were

historically forced into disadvantageous positions, and still remain so as well

as being deprived of political voices.

This leads to my second perspective, which is women’s viewpoint.

(2) Democracy by definition is a system

where we obey the laws determined by ourselves, not by others, which enables us

to be free as well as obedient. However,

as I mentioned earlier in (1), “we” are so diverse that it would constitute

nothing less than violence to put those who are different from the majority in

terms of opinions and experiences into the same basket of “we.”

In the present Constitution, in particular,

Article 97, the fundamental human rights guaranteed to the people of Japan are

described as “fruits of the age-old struggle of man to be free” which “have

survived many exacting tests for durability.”

This is the article that LDP proposes to delete in its draft of

amendment.

The present Constitution, for example, was

born out of a historical commitment to secure women’s right to equality and

freedom after many years of struggles and trials which women in former times

experienced as second class citizens.

They were deprived of matrimonial rights as well as rights of property

and education, the freedom of occupational choice, and of course, suffrage. Because of such a deprived status, women had

been treated as instruments at home, in the society and by the state.

But unfortunately, Prime Minister Abe and

other politicians who consider the amendment of the Constitution as their

political mission, still regard women as if they were latent assets or hidden assets, and even as “reproductive

machines” as I recall a certain politician mentioned just some time ago. As the plan to introduce “pocketbook for

women”[1] revealed, women are treated just as an object to be controlled for

boosting Japan’s birthrate or to be activated for economic growth, and, once a

war breaks out, as an instrument mobilized in the way comfort women were in the

past.

In other words, the important function of the Constitution is to remind us that the nation exists to prevent the state from being abused by the powerful of the time and to keep it away from human lust for power, or, equivalently, to protect the individual’s dignity. This fundamental principle of the Constitution has been meaningful particularly for those who are forced to be historically and socially weak. In sum, it is the minorities who could never form the majority that this important principle should apply to.

(3) Finally I would like to touch upon our

own being, namely how “we” can be. In my

view, the largest difference between the LDP’s draft for amendment and the

present Constitution can be found in the historical and spatial extent. Let me quote Article 97 again to reiterate

that fundamental human rights are conferred upon not only “this” generation of

today but also “future generations" in trust.

Based on the reflection and regret about the historical tragedies and

crimes committed by the state, an apparatus for monopoly of violence, the

present Constitution is addressing future generations. It vows with modesty even to those who are

unable to participate in the discussion in the ongoing “here and now” that the

state promises to protect the fundamental rights of individuals.

Furthermore, I believe that the fundamental

spirit of the current Constitutions lies in the concept of fundamental human

rights based on natural rights and that of individual dignity as is guaranteed

by the Constitution. As long as this holds

true, the present Constitution can not only address the Japanese people but

also deal with the rights of other non-Japanese people who are also part of

Japanese society. As a matter of course,

“we” include people of non-Japanese nationality who are also constituent

members of Japanese society. In this

regard, the right of foreigners to vote in local elections, which is not

explicitly prohibited in the current provisions, is disabled by the article of

nationality in LDP’s draft.

In summary, I consider that the will for

power as is demonstrated in the amendment draft of Article 96 is the will to

suffocate the life of “we, the people” who can be, and are, in fact, as diverse

as ever.

[1]

In early May, 2013, the Cabinet Office's task force suggested a plan to distribute pocketbooks among young

women with the aim of providing knowledge of pregnancy and childbirth as part

of its effort to boost the birthrate. But with growing concern about public

intervention into women’s decisions as to whether or not or when they have a

child, the plan was criticized by opposition parties and women's

organizations. As a result, it was

virtually withdrawn by the Cabinet Office as of May 28, 2013.

Original Article on WAN Website

http://wan.or.jp/reading/?p=11472

Translated and Adapted by FUKUOKA A.A